The Surface Grower Algorithm

By Steven Clark

Introduction to Surface Grower:

The Surface Grower algorithm is based on work done by David

Cohen-Steiner and Frank Da, and is described in their paper "A Greedy

Delaunay-Based Surface Reconstruction Algorithm", which

can be found here.

The description of the Surface Grower

algorithm assumes basic familiarity with three-dimensional Delaunay

Triangulations; therefore, the next section will introduce them along

with other basic computational geometry concepts. If you are already

familiar with such ideas, please feel free to skip ahead.

Computational Geometry Primer:

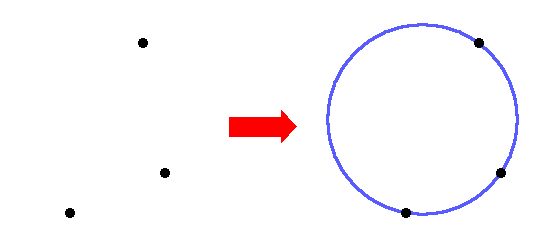

We'll start in two-dimensions.

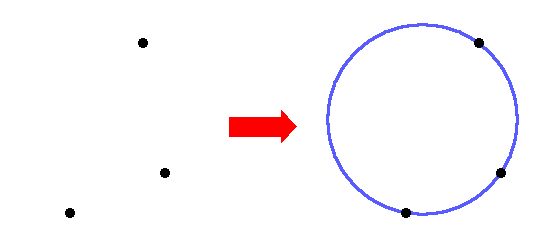

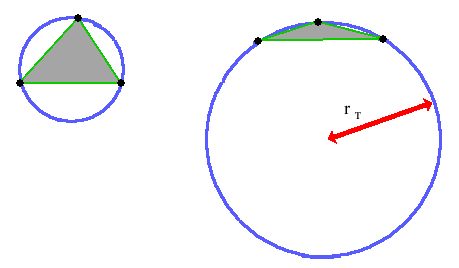

The first observation to make is that three non-co-linear points

determine a circumcircle:

In other words, for any three non-co-linear points, there is a unique

circle which passes through all three points. Hopefully this property

is fairly intuitive.

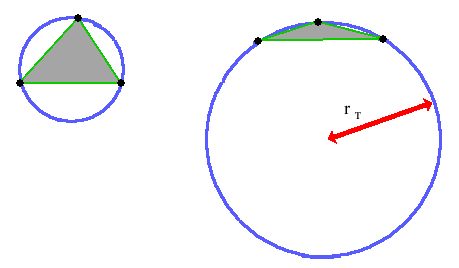

It's interesting to note how the size of the circumcircle is affected

by the shape of the triangle formed by the three points:

The triangle on the left has both a larger area and a larger perimeter,

and yet, it has a smaller circumcircle than the triangle on the right

because it is closer to being equilateral.

We're defining rt to be the radius of the circumcircle of

triangle t. This quantity will play an important role in the Surface

Grower algorithm, as we will see later.

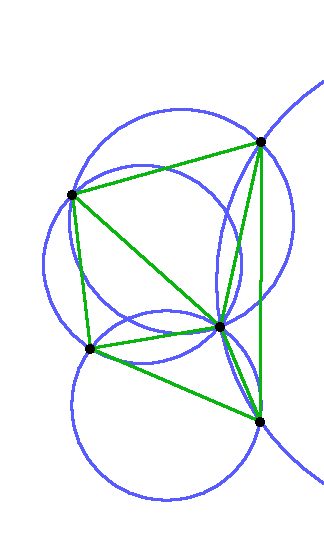

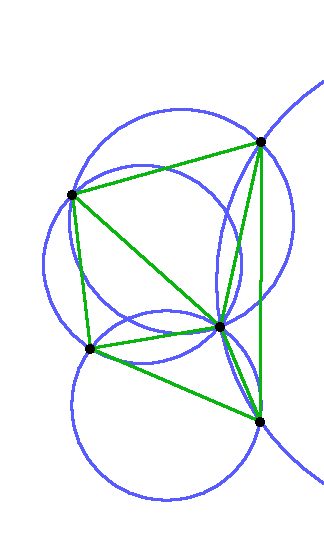

The concept of the circumcircle helps us define something called the

Delaunay Triangulation. The Delaunay Triangulation of a set of points

is the set of all triangles having those points as vertices whose

circumcircles are empty:

In other words, if you look at the circles defined by the triangles,

you can see that they contain no other sample point.

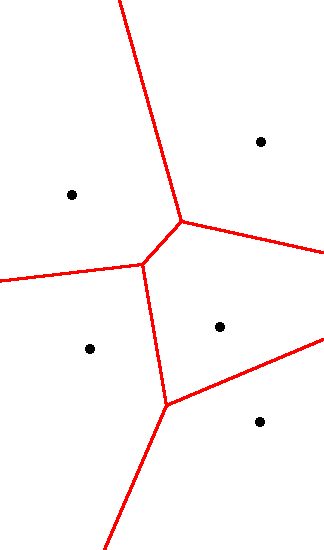

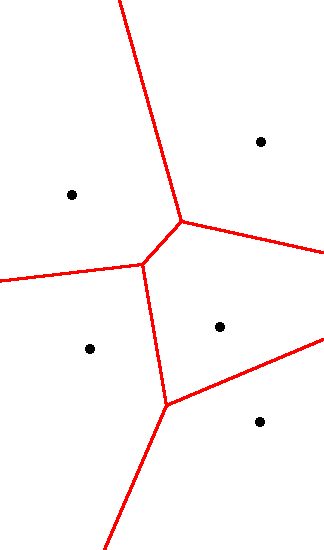

As a brief aside, the Delaunay Triangulation has a geometric dual

called the Voronoi Diagram (shown on the right):

We say that these two are duals, because they are different

representations of the same information. One can generate a Voronoi

diagram from a Delaunay Triangulation by taking the perpedicular

bisectors to each of the Delaunay edges. If two Voronoi cells share a

boundary, then they will be connected by an edge in the Delaunay

Triangulation. Also, the intersections of the red boundary lines on the

Voronoi diagram are the centers of the circumcircles of the triangles.

There are many interesting properties which arise from the interactions

between Delaunay & Voronoi, but most of them are beyond the scope

of this project.

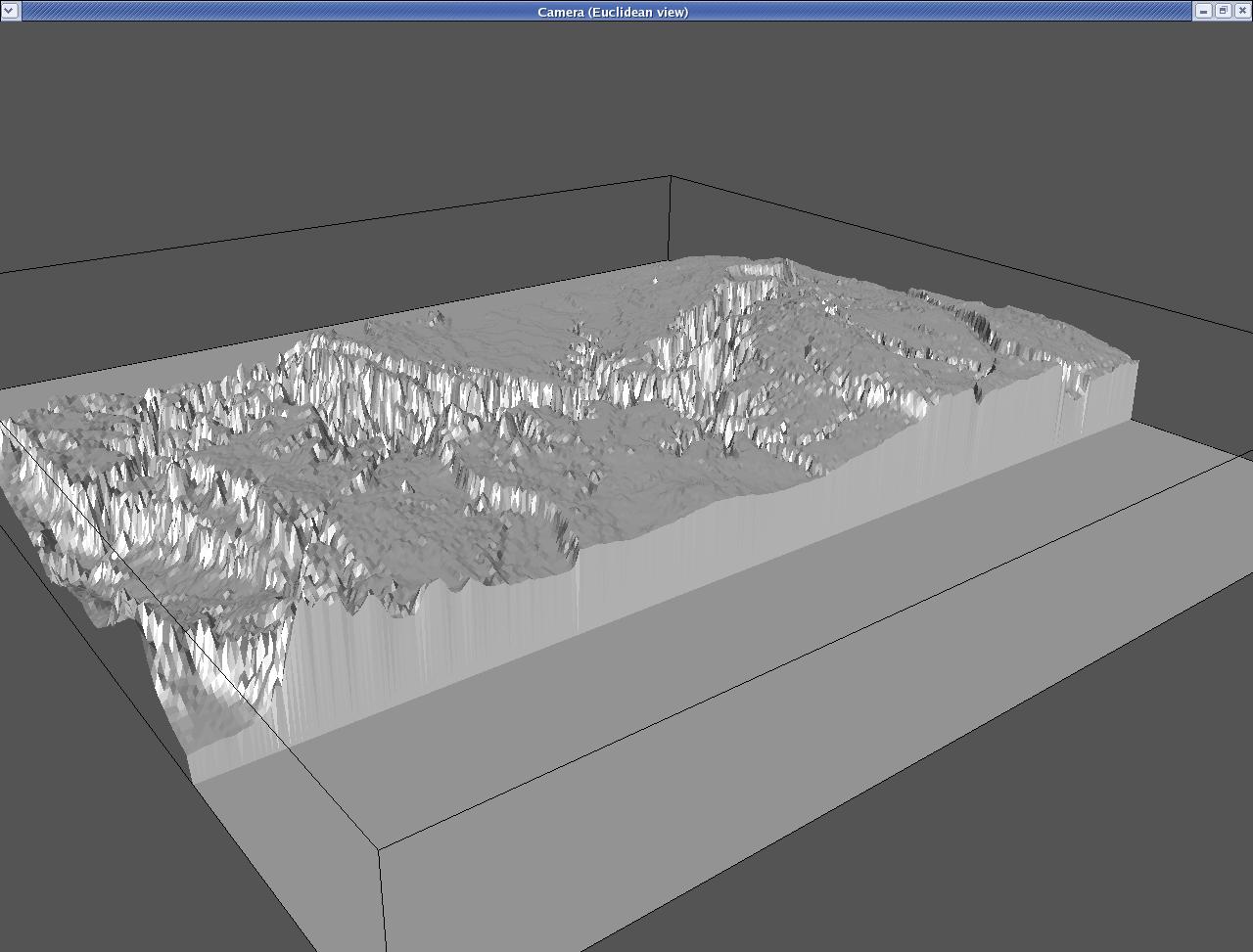

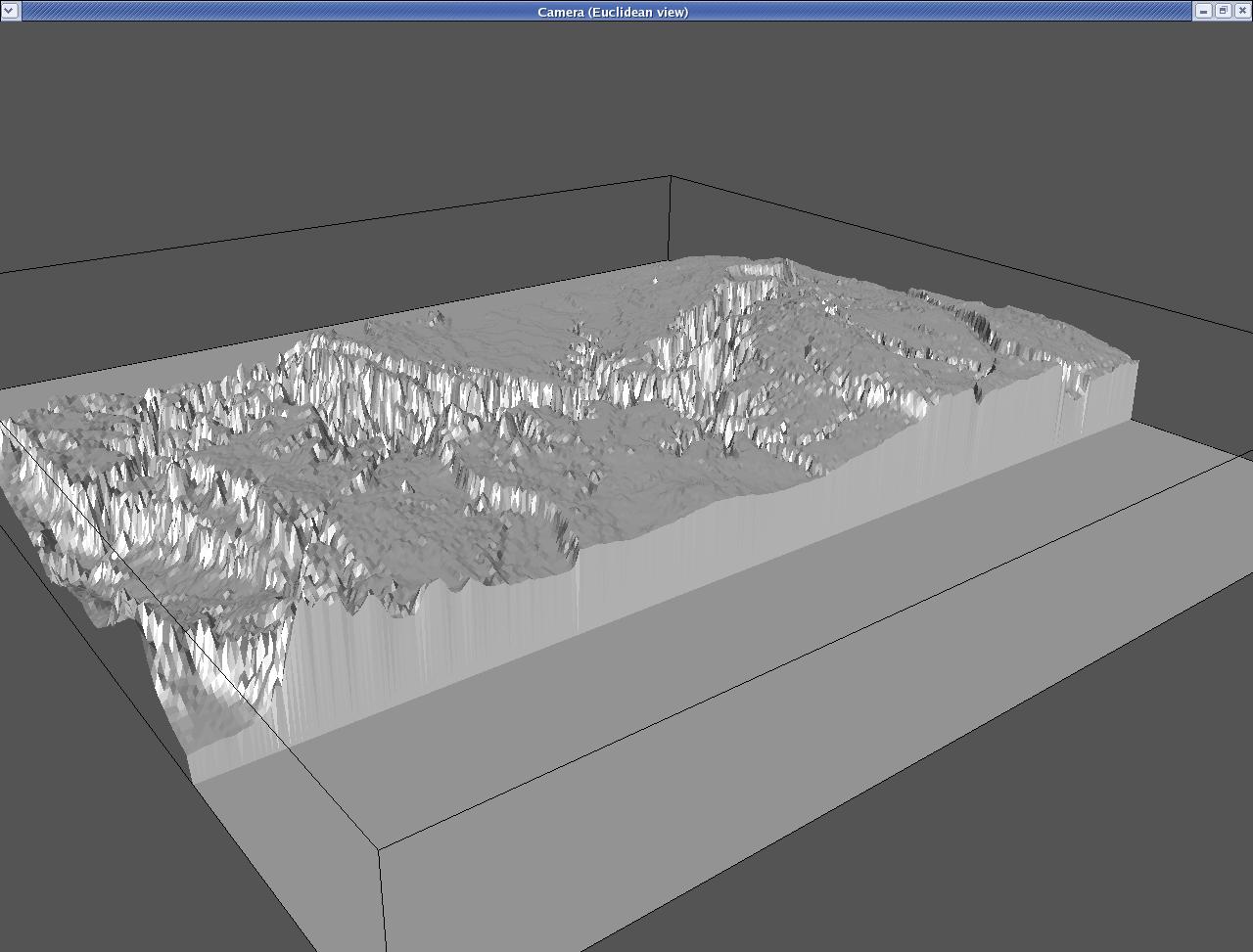

Below is a reconstruction of the Grand Canyon, done using the

Bowyer-Watson algorithm--implemented by Ben Anderson in Fall '04.

This technique ignores the z-values of the points and performs a simple

2-D delaunay triangulation to obtain the mesh. This algorithm is ideal

for topographical data, but doesn't work for a surface which crosses

back under itself.

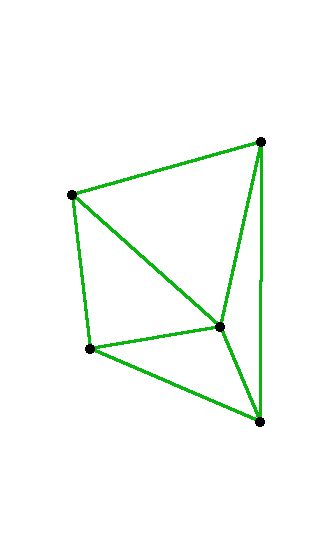

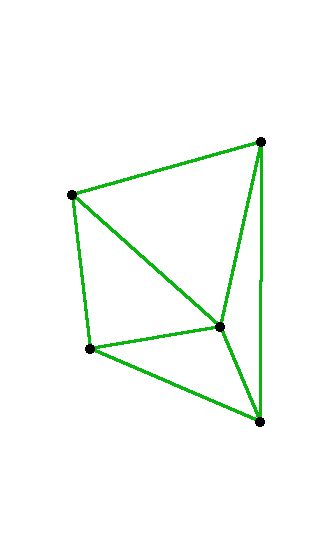

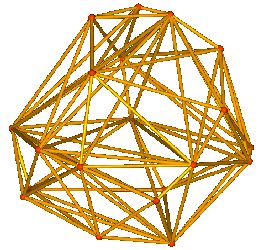

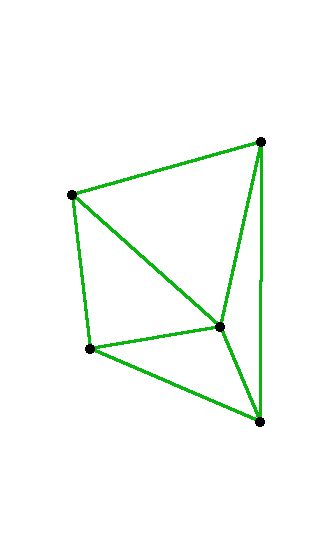

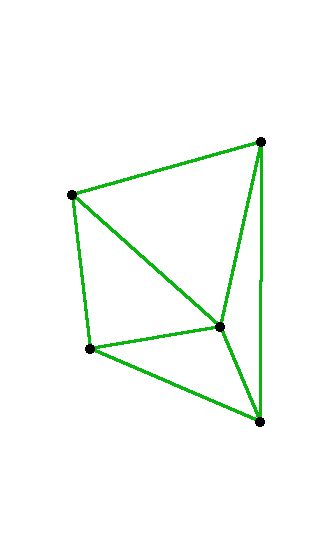

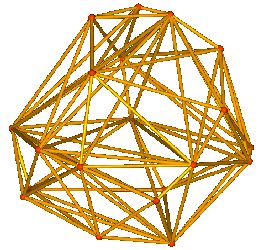

Now we're bumping up to three dimensions. Just like three points define

a circle, we find that four non-co-planar points define a sphere. A

Delaunay Triangulation in 3D is the set of all tetrahedra having those

points as vertices whose circumspheres are empty. This is an example of

what a 3-dimensional Delaunay Triangulation might look like:

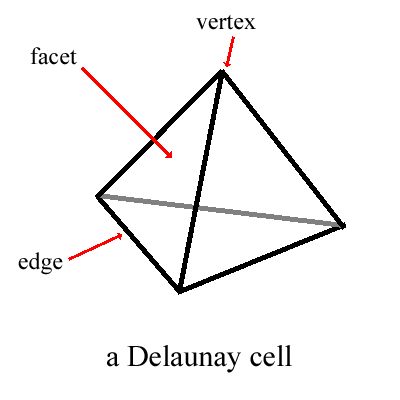

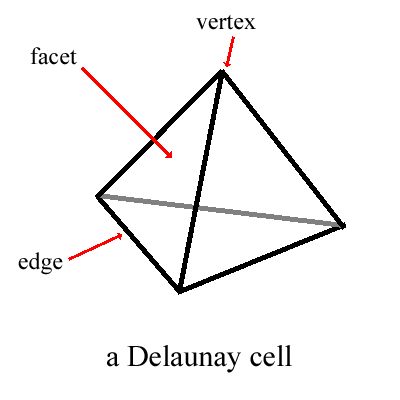

Here is a depiction of some of the terminology we are going to be using:

Each tetrahedron will be called a cell. A cell has 4 facets, 6 edges,

and 4 vertices. We'll be using the terms facet and triangle somewhat

interchangeably.

Surface Grower:

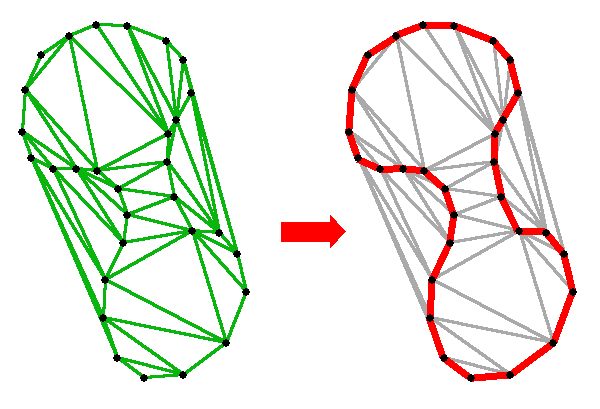

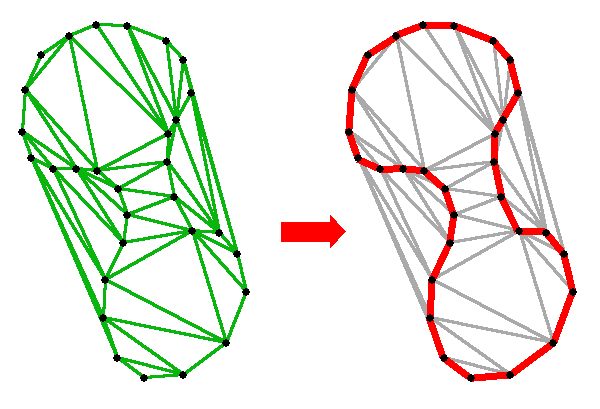

So now you know what a Delaunay Triangulation is. What does this have

to do with shape reconstruction? Well, it turns out that a certain

subset of the facets formed as a result of a Delaunay Triangulation

forms a good approximation to the original surface. A 2D version of the

algorithm (curve reconstruction) would hopefully identify the edges in

red as the best approximation to the original (admittedly odd) shape:

Therefore, the task of the algorithm could be restated as, "Given a

Delaunay Triangulation, identify the collection of facets which best

approximates the original surface." Of course, this is easier said than

done.

The basic idea behind this algorithm is that we start from a seed

facet, and grow the surface outwards from there, adding the most likely

facets first in such a way as to keep a continuous boundary. Because we

are grabbing the most likely facets first, we say that this is a greedy

algorithm.

We will first describe the technique for locating the seed facet, since

if you try to start from an incorrect facet (ie one inside the object),

you will encounter significant difficulty. Basically, we want to insure

that the seed facet is a) actually on the surface, and b) in an area of

good sampling density. We do this by finding the facet with the

smallest circumcircle. In other words, we iterate through all facets

produced by the Delaunay triangulation, and find the one with the

smallest rt.

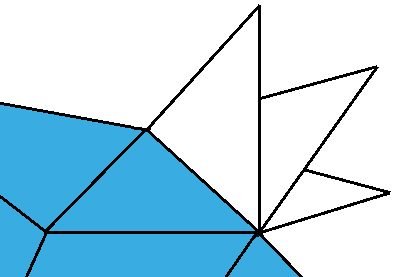

So now that we have the seed facet, we can start growing our surface

out from there. At this point, our surface consists of one triangle and

three edges. For any given edge on the boundary of the current surface,

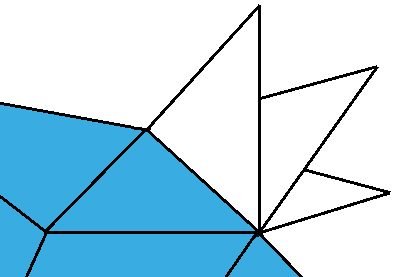

there are going to be many incident facets:

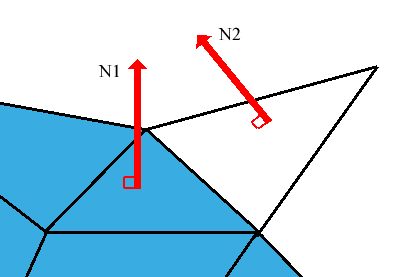

For each edge, we're going to have to determine which of those facets

is going to be our candidate facet. One useful thing to look at is the

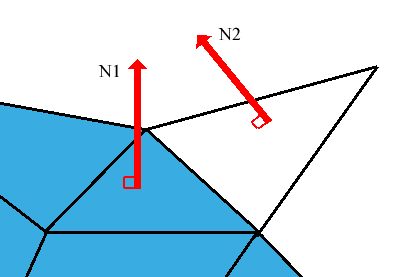

dihedral angle between the facet you're looking at and the adjoining

surface, i.e. the angle between normal vectors 1 and 2:

You expect this to be small when the sampling density is good. So the

incident facet with the smallest dihedral angle becomes our candidate

facet for that edge.

To choose which of the candidate facets to add first, we need a metric

with which to compare candidates against each other. We rank them

according to their plausibility grade. Two factors go into the

plausibility grade, those being the radius of the facet's circumcircle,

and the dihedral angle of the facet. The relationship is shown here:

[fix me]

The idea behind the 30 degree threshold is that for sufficiently small

dihedrals, the dihedral becomes less of a meaningful metric (especially

in the presence of noise), and so we switch over to using the radius to

determine the plausibility of the facet.

There are four main data structures we keep track of: The Delaunay

Triangulation, a vector of the triangles we have selected thus far, a

linked list of Boundary Edges, and a priority queue of candidate

facets, sorted by decreasing plausability. At all stages of the

algorithm, we have to keep these four up to date and correct.

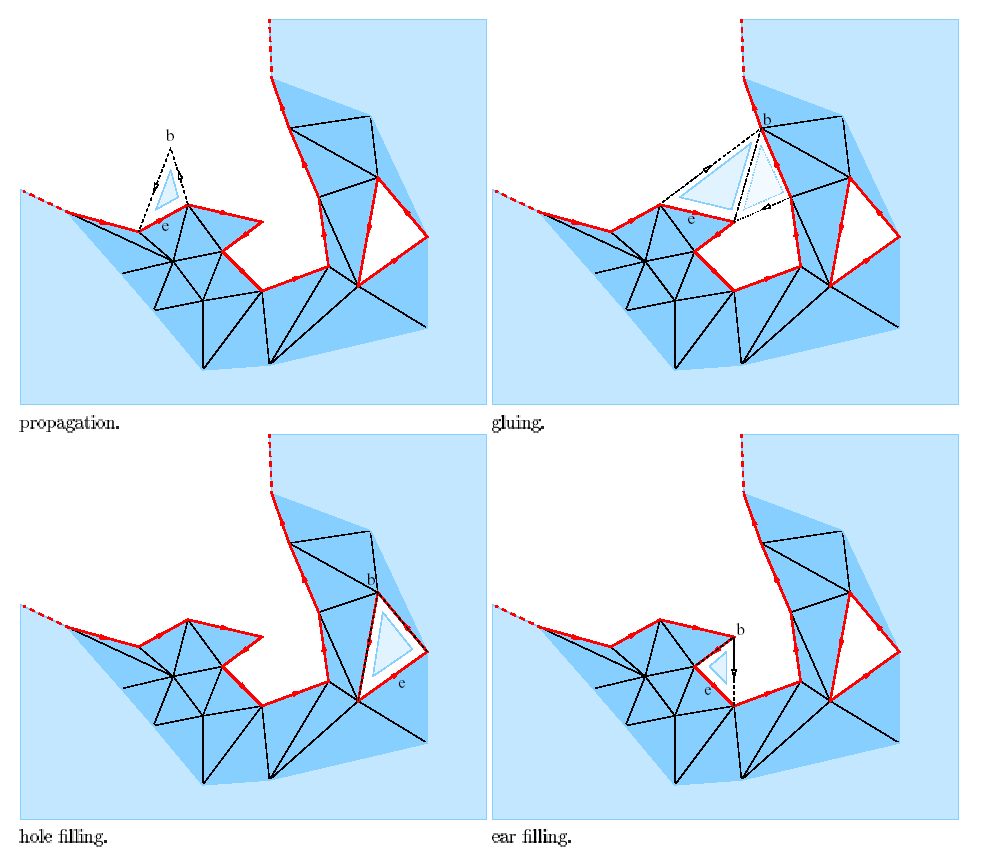

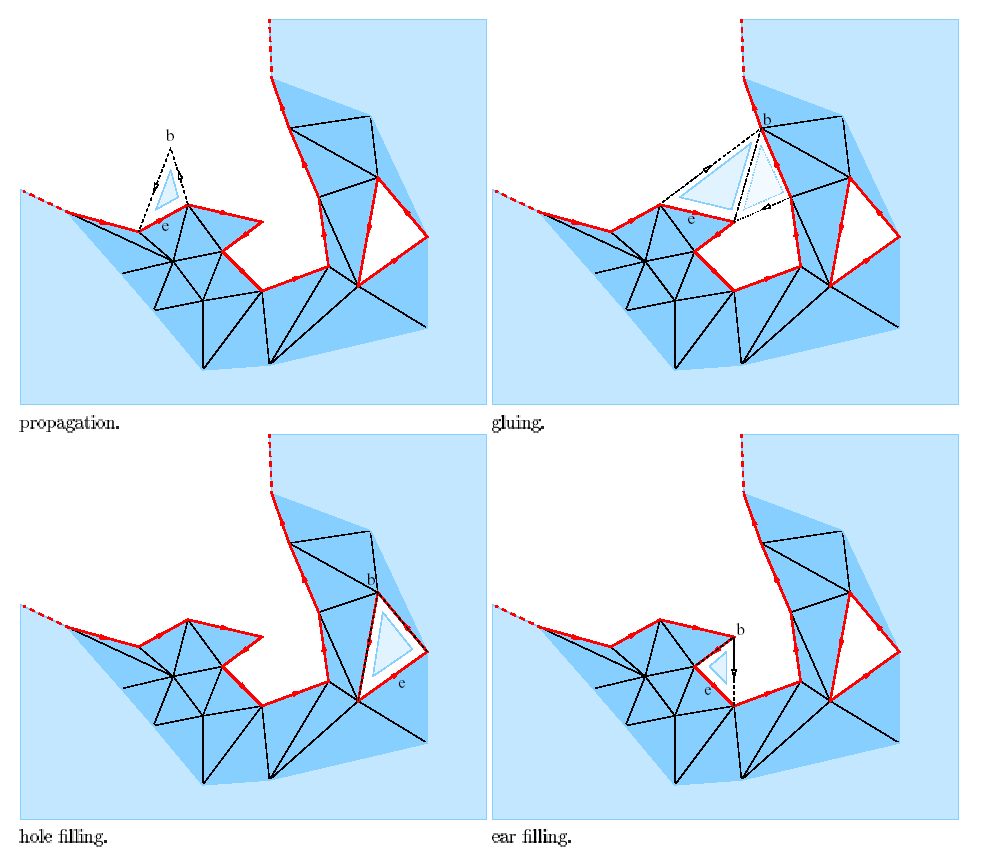

With the priority queue of candidate facets, we can repeatedly pop off

the facet with the highest plausibility and attempt to stitch it to the

rest of the surface. There are four types of stitching that are

allowable, as you can see up here:

Analysis:

The primary strengths of Surface Grower are due to the simplicity of

the input requirements; all you need is a list of x, y, z values for

points on the surface of the object; this type of data is frequently

obtained from a laser-range scanner. Another nice feature is that the

input data doesn't have to be constrained to parallel planes: point

clouds are ok. And finally, little to no post-processing is required.

The weaknesses of the algorithm are that it is reliant on the

feasability of computing a 3D delaunay triangulation. This can be a

very computationally expensive task; in our case, we used the open

source library CGAL to accomplish this task. Generally, CGAL seemed to

be reasonably snappy and robust.

You also are not guaranteed to get a watertight model. Depending on

your application, this may or may not matter. And finally, some manual

tweaking is required for non-continuous surfaces; essentially, you have

to tell it what kind of sampling density to expect.

Results:

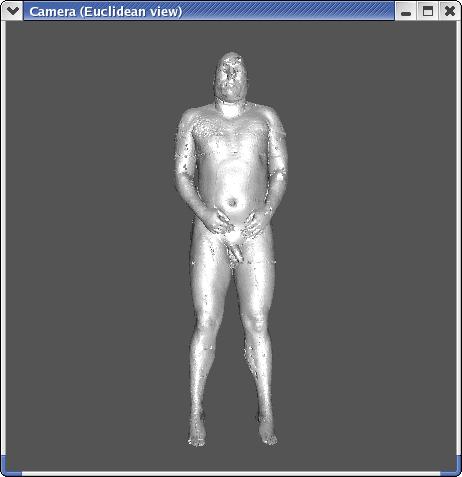

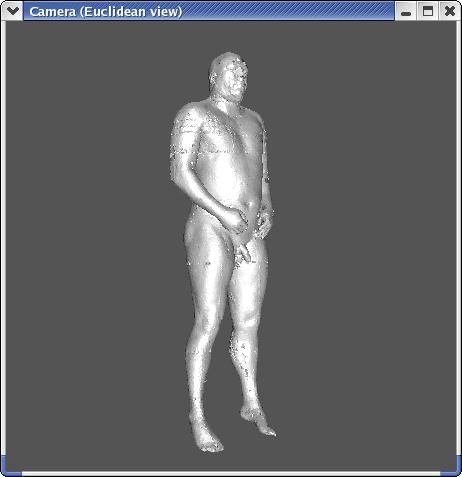

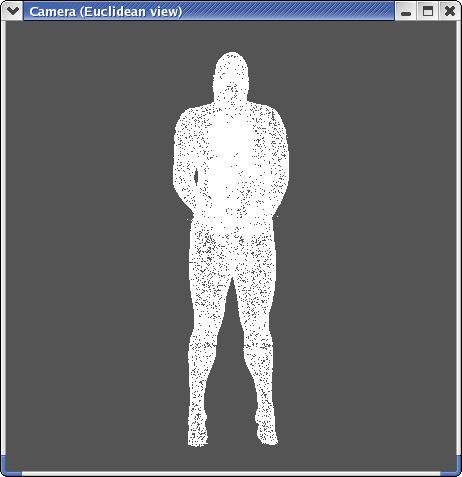

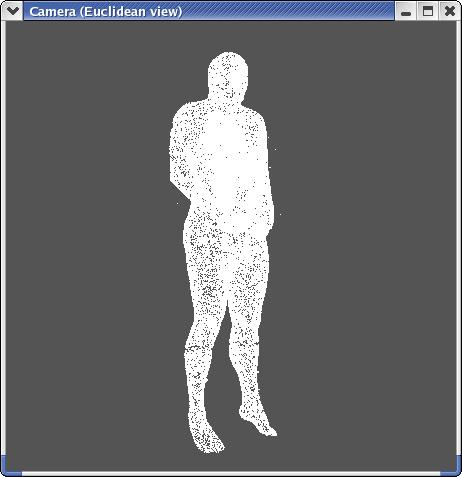

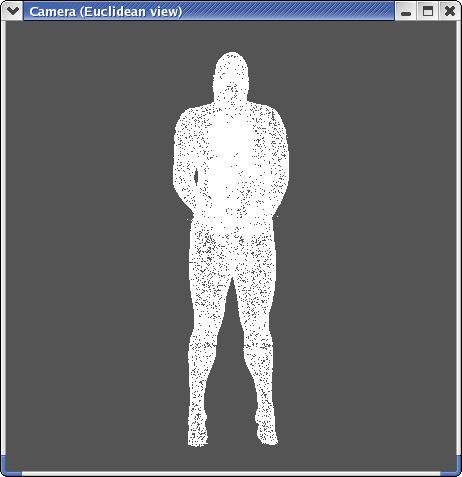

Input to the algorithm:

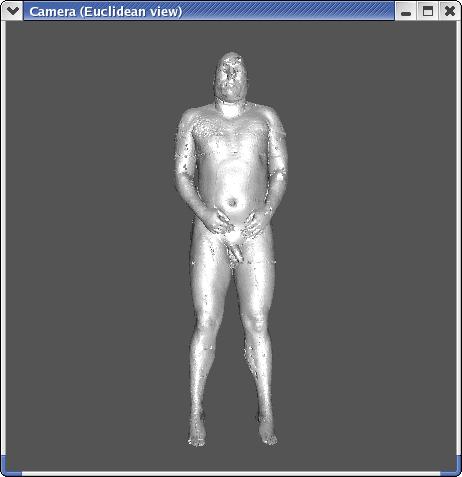

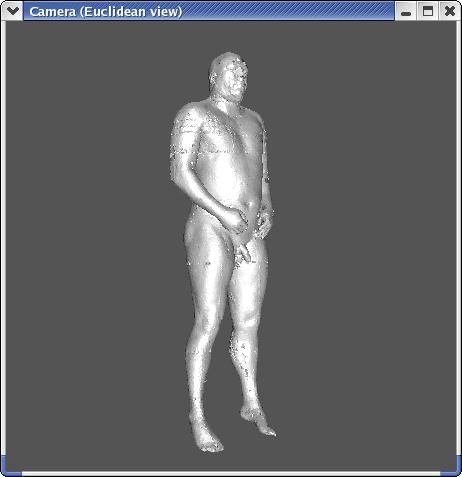

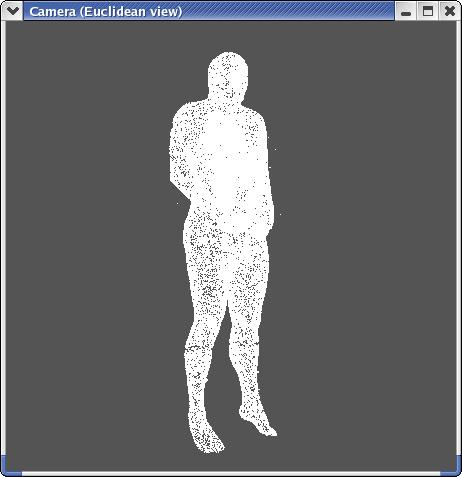

...and triangulated output: